Educational Leadership, September 4, 2013

Kirsten Olson, Ed.D., PCC

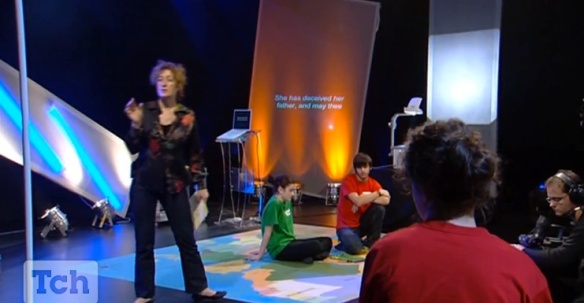

Master coach/conductor/teacher Sabrina Broadbent introduces Othello to 9th and 10th graders on Teaching Channel.

Renya Santiago, a principal at a urban charter middle school in Delaware, is frustrated by flat-lining state test scores at her school, and underperformance on formative tests she and her teachers administer at their all-girls charter. “The mission of this school is to create the future’s much-need female leaders,” Renya explains when my consulting partner and I meet with her for the first time. “Yet in base-line accountability measures, we are not making the grade. We also notice the girls being too passive in class, not willing to step up intellectually. It frustrates us that they won’t take more responsibility. We’d like them to be more creative and bold, and the new Smarter Balanced Assessment Delaware is using next year will demand that they are.” And yet, when my consulting partner and I begin observing classrooms, we wondered: what are we doing in class that would build that intellectual creativity and cognitive inventiveness?

In a delightful 2012 video, renowned comedian John Cleese described his own ideas about how to get people into an “open” cognitive space, the seat of creativity, in Cleese’s view–and also how not to. Cleese outlines three absolute, surefire ways to guarantee people won’t be creative, inventive, and intellectually self-confident: bar humor, make sure everyone knows how important you are, and especially, make sure everyone is constantly busy. “So demand urgency at all times, use lots of fighting talk and war analogies, and establish a permanent atmosphere of stress, of breathless anxiety, and crisis.” Do these things Cleese observes, and you’re certain to have a lot of unhappy, closed, un-creative people [and students] around you.

Okay, hold up. On our bad days, perhaps even on our normal days, isn’t this a bit how we position ourselves at school? A tad humorless? (This is not funny, this learning thing!) At the front of the room (or the meeting), letting everyone know who’s in charge? (Excuse me, but you just interrupted my monologue.) And most especially, aren’t we often urgently, breathlessly busy almost all the time, and insistently demanding that everyone else be as well? Don’t we frequently communicate that learning is a deadly serious business that must yield to high value “targets” (military analogies) and benchmarks? And don’t we often assume too that instruction requires lots of monitoring, anxious oversight, and tension-filled assessment–or for gods sake it will never get done!

Given what we know about intellectual-risk taking and creativity: that being creative and intellectually adventurous requires projecting ourselves into a cognitive and emotional domain where we are able to–and give ourselves permission to–incubate novel ideas, often for no explicit purpose at all[ii]–how do we transition out of traditional classroom or educational environments that inculcate intellectual passivity, reward rule-following and compliance to teacher-instantiated values which locate authority for know outside of the student? How do we move to classroom environments that promote playfulness, experimentalness, engagement, and encourage students to make mistakes, to think for themselves, and to be intellectually entrepreneurial?

COACHING AS A NEW MODEL FOR TEACHING

Here’s where a new paradigm for teaching enters the room. (Hello Coach!). Beginning in the mid-1990s, coaching, a method of interacting with another person to help them identify critically important values, to explore new ways to think and behave, to achieve cherished personal and professional goals, and to feel more vibrant and present, has surged to popularity and credibility in business, medicine, academia, and in virtually every high-performance sector.[iii] Coaching as a way of improving performance has grown exponentially over the last decade (2012 ICF research estimates there are almost 50,000 professional coaches worldwide[iv]) and is becoming increasingly sought out among heart surgeons[v], C-suite executives, and even in the superintendent’s office and teacher’s lounge[vi]. The International Coaching Federation (ICF), the world’s largest coaching credentialing body organized to create a worldwide network of trained, certified coaches, defines coaching as “an ongoing professional relationship that helps people produce extraordinary results in their lives [and] careers,” by encouraging creativity, engaging clients in self-generated solutions to problems, and by supportively holding the client responsible and accountable for new behaviors and actions.[vii] But coaching as a paradigm for transforming the pedagogical relationship between student and teacher, in order to promote creativity, initiative, and the much-touted 21st-century skill set, is just beginning to take hold as professional coaching’s fundamental precepts[viii] are more widely understood. Although great teachers everywhere have always assumed the competence, resourcefulness, and wholeness of every student–indeed see this as the center of the relationship–teachers conceiving of themselves specifically as “coaches” instead of traditional teachers–is a relatively new, yet incredibly promising approach. Why?

Professional coaching rests on several fundamental principles: it assumes that the person, or set of individuals one is interacting with, is already skillful, wise, and has a profound desire to learn and to achieve the goals they feel are important. It also assumes that most of us find reflection, experimentation, and accountability helpful in achieving our goals. The stance of assumed competence and resourcefulness on the part of the coach, “the belief part” is critical, and a significant departure from the conventional teaching relationship, which presumes that students “lack” something that the teacher must “give” them. Or as Paulo Freire described it, in the hierarchical, banking method of education[ix]–in which the teacher knows and the student is to know–is still a pattern very widely abroad and instantiated in the lived patterns of teaching in our country. To be a professional coach, as I experienced when I became trained and certified in a professional coaching program after years of consulting and teaching, means giving up the all-knowing stance of the paid consultant, and even the knowledge-bearing mantle of the teacher. You become the inquirer, the question-asker, the curiosity fomentor. When you coach, you stop giving advice and stop thinking about what you know, and start getting really curious about what is going on with the other person (or people). In their excellent little book on coaching conversations in school, Linda Gross Cheliotes and Marceta Fleming Reilly (2010) note that, “Coaches operate with an underlying assumption that giving advice to others undermines the confidence and self-worth of others. Others don’t need to be fixed.”[x] In teaching we need to move to exactly this stance in order to foster creativity in our students–to allow our students the choice, control, novelty and challenge that builds their creativity–the essential conditions as defined by Csikszentmihalyi and others. Without the assumption that our students are already competent, imaginative, and ready to burst forth with regular exhibitions of novel and valuable ideas and products[xi]–we are limiting their creative capacities before they’ve even had a chance to discover them. As Lou Cozolino’s (2012) wonderful new book on the social neuroscience of education makes clear, how we feel about our learning environments, and the assumptions that are made about us as learners within them, dramatically affect our brain development and our capacity to produce creative and novel work products.[xii]

What a difference the stance of competence, wholeness, and creativity make. A colleague of mine in my doctoral program once described her oral exams with a committee of particularly obstreperous academics at Harvard. Her committee chair and someone who knew and loved her work sat on her left. At her right a doubting, difficult, knowledge-guarding interrogator. My colleague said she turned left and was brilliant. When she turned right, “I was the block-headest person ever to take an oral exam.” Assuming the stance of competence and invitation to learn, as a teacher–no matter how restrictive the system of education in which we must work–can dramatically and palably transform teacher student relationships and student capacity. (And possibly our deadly systems of education to boot.) This means, in practice, moving from giving advice to students or giving them answers, to creating awareness of what they want to know and helping them design actions to achieve their learning goals. (Giving them practice being creative!) This also means not offering options for learning, but encouraging learners to design possibilities themselves, and then insisting students themselves plan and goal-set, monitor their progress, and then analyze what worked and what didn’t. (Celebrate! That’s creative!)

WHAT A COACHING STANCE LOOKS LIKE IN A CLASSROOM

As mentioned extraordinary teachers have always viewed themselves as coaches of students. In the past “gifted” education has provided a model for this approach in its playful, inventive invitations to learn, and assumptions of competence on the part of the learner. (What if we regarded all students as gifted?) Paula White, a longtime elementary school teacher in Albemare County, Virginia observes about her own stance as a highly successful teacher, “In my 38 years of teaching, where I have taught all grades K-5 in every combination, I always begin with an assumption of competence. That means we believe kids–learners–are competent and come to us with strengths and knowledge and skills and talents and curiosities and yearnings and expertise and questions, and it is my job to discover what those skills and talents are. (And in doing so I always discover new capacities within myself.) Moments that confuse or astound me give me an opportunity to explore my beliefs and understandings. I like to change of my surroundings and to explore new grades and schools as visits away from my comfort zone allow me to widen [my] view of what’s possible.” [xiii] Like a professional coach, Paula begins with the belief that her learners have a lot to teach her, and she gets the privilege of playing with them and helping them achieve their learning goals throughout the year. One of the most creative and widely respected teachers in her region, Paula was one of the first Apple Educators to be recognized on the East Coast and leads a lively blog on transforming teaching. Long time charter school leader and teacher Chad Sansing also notes, like a coach, that the key to unleashing creativity in students is giving up his claim as knowledge authorizer. “I feel very self-conscious, selfish, and unsure writing this, but I wanted to share what happened today [in my classroom] because if I have anything to offer (besides the occasional oblique reference or terrible pun), it’s an approach to teacher failure that remains open to student success. The best I can do is to be delegitimized as an authority-figure and known as a person and learner by my students. The work isn’t there to isolate resistant students, to assert my control, or to protect my feelings like a curtain wall; it’s there to be torn to pieces and remixed or discarded as we build our relationships and community together.” [xiv]

Paula and Chad’s coach-like stances: assuming competence on the part of every learner, believing their roles are to create positively-charged and accountable space for learner growth, and giving up their authority as “knower,” all point to the power of the professional coach in the classroom, and its social justice implications. Discovering and clarifying what the client/student wants to achieve, encouraging self discovery, getting the student/client generate solutions and strategies for solving problems, and holding them responsible for results, upends and rebalances the traditional student teacher relationship. When I am working with a group of teachers as a coach I often pose the question, “What if the students looking up at you from the classroom didn’t need anything from you? What if you assumed they weren’t lacking anything? How would that change about your job as teacher?”

So I ask you: how might a professional coaching stance help make your classroom or school a more creative space?

_________________

Kirsten Olson, Ed.D., PCC is Chief Listening Officer at Old Sow Coaching and Consulting, in Boston, MA, which provides leadership coaching to some of the largest school districts in the country. She is author of Wounded By School, Schools As Colonizers and the forthcoming The Mindful School Leader. She is an ICF certified coach and a graduate of the Georgetown Leadership coaching program.

[ii] Csikszentmihallhy, M. (1997). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York, Harper Perennial.

[vi] Cheliotes, L.G., Reilly, M.F. (2010). Coaching conversations: Transforming your school one conversation at a time. Thousand Oaks, CA. Corwin.

[x] Cheliotes and Reilly, p. 9

[xi] Howard Gardner’s definition of creativity: p. 35, in Gardner, H. (1993). Creating minds. New York, Basic Books.

[xii] Cozolino, L. (2012). The social neuroscience of education: Optimizing attachment and learning in the classroom. New York, Norton. Forthcoming.